The Difference between "Freedom" and "Liberation": A Passover Interlude

Reflections on Aaron Shmuel Tamares’ essay “Herut/Liberty” (1906) and the present moment.

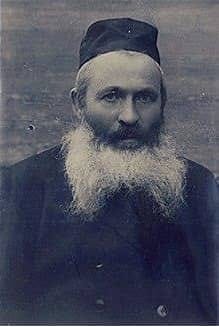

In 1906, two years after Herzl’s death, a year after the first Russian revolution, and a few years since Aaron Shmuel Tamares (1869-1931) returned despondent from the Fourth Zionist Congress in London in 1900, he published an essay entitled (“Herut” – “Liberty”), an extended meditation on Passover as a “festival of liberation.” It was his first, and perhaps most sustained, essay on pacifism in the Jewish tradition, a subject that would occupy his thoughts for the remainder of his life.

I begin my reflections on part of Tamares’ essay with a caveat to better understand his social and intellectual context. In much of Tamares’ work he constructs his proximate critique of the Judaism of his time by means of a Jew-Gentile binary. I make no excuse for the superficiality of such a binary, nor its application. Tamares uses it, as I read it, for polemical purposes, although he might have believed it more than I do. That is, he opposed the notion coined by Zionism of Jews becoming “like all the other nations,” suggesting that the quest for normalcy, while understandable, was both an error as well as an abandonment of the very thing Judaism could offer the world. In short, he believed that being “like all the other nations” was a usurpation of being a “light to the nations,” a price many early Zionists were willing to pay for sovereignty. For him, the binary of Jew-Gentile (Judaism-Christianity) with all its fissures and inaccuracies, works to caricature the European world around him in need of repair and construct his claim that Judaism could make a contribution to that broken world, of which it was a part, if it did not succumb to its own internal distortions and the failures of European collective existence.

Yet his is not a sweeping critique of the Enlightenment and its byproducts (i.e. freedom – hofesh). Modernity certainly provided an evolved state of human existence for Tamares, one that also contained its own deep shortcomings (think, for example, of Adorno and Horkheimer’s thesis in The Dialectics of the Enlightenment). He firmly believed that Judaism contains the resources, structurally and substantively, to contribute to that development and circumvent some of the pitfalls that he witnessed in the rise of nationalism and violent revolution. In the beginning of his essay “Herut” which is mostly devoted to a critique of ideological/political violence, he offers an interesting intervention founded on the distinction between the freedom indicative of European society of his time, and the liberation that stands at the center of the Jewish experience of the exodus.

*

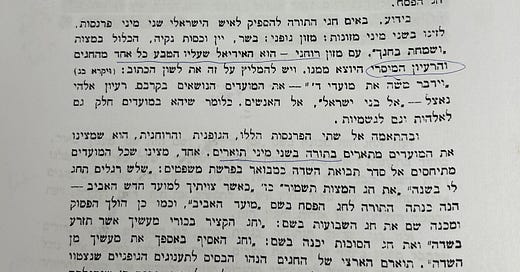

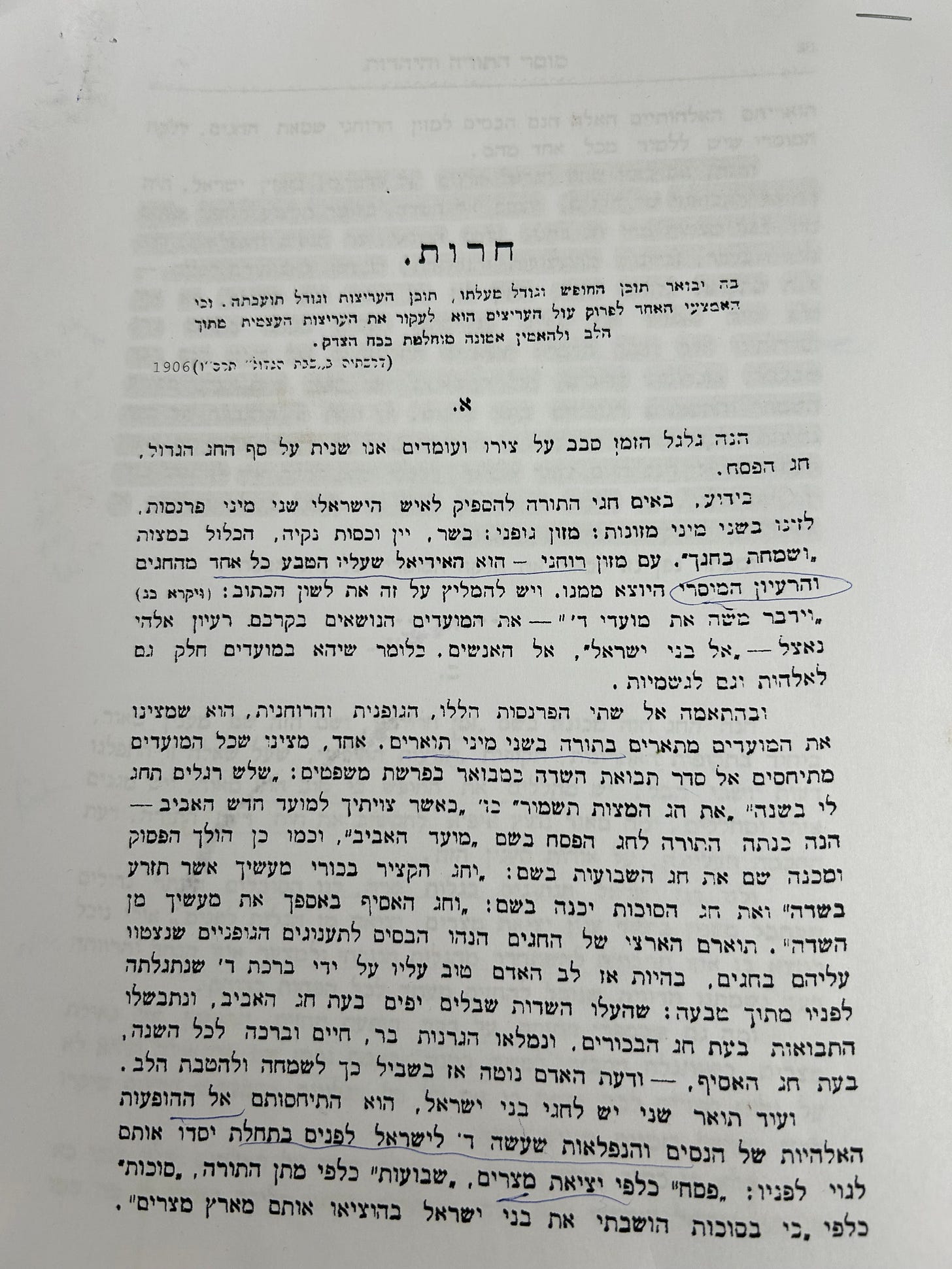

The distinction running through this essay is between “freedom” (hofesh) and “liberty’ (herut), the former a product of the Enlightenment, signaling the fall of absolutist empires and the rise of populist movements and democracies in Europe, and the latter, “herut,” a Jewish notion of liberation and, in his view, the signature ethos of Judaism. Both hofesh and herut are positive phenomena for Tamares, but they are not identical, and the distinction for him is what marks the distinctive character of Judaism. He writes:

“This festival (Passover) is ‘the time of our liberation’, a very interesting notion especially in our time, the time of “freedom.” On this notion of freedom there are many opinions, some view it is very positive, others as negative. How is this idea viewed in the Jewish tradition? (“Herut” 30).”

Put otherwise, how do we distinguish between the human freedom of modernity (hofesh) and the liberatory experience of the Exodus (herut).

Here Tamares introduces a distinction that I find both interesting and painfully relevant, a distinction between how the Jews celebrated festivals in the land, and how they were celebrated in the Diaspora.

As a preface, it is well-known that the major festivals as described in Scripture always have two components, an agricultural one, and a historical/miraculous one. Passover is the spring wheat festival, Shavout the first fruit festival, and Sukkah the fall harvest festival. In this sense Scripture relates that the Israelite calendar mirrored other civilizations that shared those times for celebration. Scripture also places “historical” elements unique to the Israelites, Passover as the celebration of the liberation from Egypt, Shavout as the giving of the Torah at Sinai, and Sukkot as a celebration of God traveling with the Israelites in the desert. Tamares will draw out different elements from this agricultural/historical paradigm.

“When the Jews resided in the land, the agricultural, physical nature of the festival was primary and present. The spiritual nature of the festival, the miraculous intervention of God in history, was viewed as something from the past, the memory of salvation that was bequeathed to our ancestors.”

“But in our present state of exile when we don’t have our own fields and orchards [to celebrate the harvest], when we don’t have the light, and even the air we breathe is attenuated [by others], in our time, things have become just the opposite. The agricultural element of the festival is now a thing of the past, given to memories of an ancient world, a memory that has become weakened with the passage of time. Today that source of joy and physical pleasure has diminished. In its place, the miraculous elements that carry with it ethical implications have strengthened. The focus now is on remembering the earlier miracles that were done for our people and how they are needed today, to learn from them to know how to act in our daily lives. This is because our ethical sensibilities are the very foundations of our existence in this exile and without them “we would not be able to be sustained, even for one hour.” (“Herut” 30).”

Later in the essay he distinguishes between the “freedom” of the nations and the “freedom” of the Jews. The experience of freedom more broadly is often expressed as independence. But for him this is a mistake.

Freedom is often seen as earned and not the product of a gift. However, we can see a difference between the acquisition of freedom of the European nations and how we Jews understand/enact freedom. They “take freedom” such as in the French Revolution, by rebelling against one despot or another. Alternatively, we “take freedom” through the Seder, eating matza, reciting Hallel with our families. That is, on our lips is the remembrance of freedom through the exodus from Egypt. So, let us consider: which of the two types of struggling for freedom yields better results?

For Tamares the biblical phrase “be joyous in your festivals” (ve-samakhta be-hagekha) was specifically directed to the physical sustenance one’s enjoys from the spoils of landedness, the fruits of harvest, and the experience of a festival. The historical, miraculous dimension of the exodus, etc. that it, the memory of divine liberation, is something from the past and are thus secondary.

However, when Jews are not in the land, that is, when they are in exile, the physical enjoyment becomes secondary (it becomes an object of remembrance), and the miracles of the festivals become primary. The purpose of divine intervention morphs into the evolution of morality whereby liberation is not viewed as a product of human agency but as a divine gift. Hence instead of celebrating “like other nations” with fanfare and exhibitions of power (e.g. military parades), we sit with our families and tell the story of liberation via divine fiat.

This for Tamares is the basic distinction between Enlightenment and nationalist “freedom,” and Jewish “liberation.” True liberation for him does not begin with the exodus from Egypt but with Moshe’s encounter with the divine presence at the Burning Bush. Tamares writes, “This hints that this redemption (geulah) is not only about the liberation from Egypt but from all the ‘redemptions’ the Jews will experience throughout history.” The exodus from Egypt is its first instantiation.

Tamares’ distinction between “freedom” (hofesh) and “liberation” (herut) between European autonomy and Jewish morality, offers and interesting inversion of landedness verses exile, not from the perspective of Jewish bodies but from the perspective of the Jewish conscience. Or, perhaps, not from the perspective of power but from the perspective of morality.

Interestingly, the Enlightenment offered us a new understanding of morality as a humanly generated sense of collective life through Reason. Yet this very Reason - remember this is 1905, a year after the first Russian revolution, and a few short years before the Young Turk revolt in 1908 - also created a sense of collective power that in less than a decade would destroy Europe. The freedom of morality morphed into the freedom to assert power over others.

As Tamares presents it, the biblical description of Jewish festivals, originally framed as agricultural with a subsidiary component of history/miracle, provided the Israelites with a sense of a double meaning: first, like all civilizations around them, an occasion of thanks for substance and safety in their harvest. And second, a historical/miraculous (perhaps mythic) sense of the moment as a product of divine beneficence. In times when the Israelites lived in the land, the former was primary and the latter, secondary. Thus, he reads the biblical locution “be joyous in your festivals” as referring primarily to harvest.

When Jews lost their land, the priorities of the festivals were inverted. The historical/miraculous became primary and the agricultural secondary. For him, this provided the Jews with a distinctive opportunity that can only be achieved by a de-territorialized collective. The focus on the historical/miraculous elements served as kind of moral training whereby the collective would develop a recognition that power is always a dangerous tool in the ones who have it (in the case of the Jews, through the experience of victimhood), and that power can be better expressed through a sense of one’s own powerlessness.

[As an aside, this is also an interesting way to understand why the sages choose the story of the miracle of the oil story on Hanukkah instead of celebrating the military victory of the Hasmoneans.]

This, he suggests, serves a s the contribution the Jews could make to a quickly nationalizing society in Europe where power through “freedom” was being deployed in destructive ways. That is, when the power of nationalism is void of a moral barometer that the historical/miraculous dimension of the Jewish festival provides. Later in the essay he argues this results in intellectual/ideological violence rishut sikhli) justified by means of power as a tool of control.

His critique of the Jewry of his time is that the opportunity of a return to the land through Jewish nationalism poses a serious challenge for Jews to return to the land with an evolved sense of moral sensibility that was the product of their exile and not use victimhood as a justification of power. Thus, the Zionist notion of “negating the exile” was anathema to him, not only an error but dangerous, and pointed to the ways in which Jews were abandoning the very aspect of their historical existence that could provide a “light to the nations.”

After attending the Zionist Congress in London in 1900 Tamares returned home despondent and disappointed at the expression of overt nationalism and the lust for, and intoxication of. power that he experienced there. This led him to the conclusion that Zionism was making the same mistake as the nationalisms around him. Instead of retaining the sense of the miraculous that produced humility through cycles of collective festival as a landless people, the Zionists he encountered in London were becoming seduced by the potential power of a landed people and, wanting to become “like all the other nations,” would indeed succeed in that. In doing so, however, they would abandon their destiny.

*

It is difficult to celebrate the Seder this Passover without thinking about how Tamares may have been right. The worst kind of violence for Tamares is not the violence of desire or passion, or even anger. The worst violence is the ideological violence that is justified through myriad arguments, including ideological precepts that are veiled under the guise of security. In those cases, Tamares argues, violence is justified only when the “false” becomes revamped as the “true,” convincing a collective that committing acts of violence is not only justified but necessary, even praiseworthy. When such an ethos becomes embedded in a society it is hard to excise it.

As we witness such acts of violence in Gaza that are committing politicide and sociocide, the utter devastation of an entire society, and we listen to all the justifications, rationalizations, and bromides about our people’s “innocence” in the deaths of tens of thousands of civilians, I submit we are witnessing Tamares’ inversion of the “false” and the “true.” How do we recite at the Seder, “all who are hungry, come in an eat,” when we are starving children in Gaza (and to make it worse, some of us are denying we are doing it). And anyone who dares disagree, becomes the enemy.

In a sense, we should ask at the Seder whether our return to the land has not only reversed the inversion of primary (a landed, material, agricultural, presentist celebration) with secondary (historical/miraculous) but in fact enslaved the miraculous to power – not God’s power, our power.

I think the inversion of “false and “true” may be even deeper than we think. The nation of Israel, the “Jewish state” is not becoming more religious. As I read Tamares, the nation of Israel is becoming less religious, in the most egregious way by using religion as a cudgel of power, as a weapon to justify killing innocent people. The people themselves can also become an idol. Tamares writes in Knesset Yisrael in 1921 “eretz moledet zu avodah zara” (the homeland can also be idolatry). Miracle in the service of brute force. God in the service of human depravity.

Tamares predicted what was coming in 1905. By 1914 Europe would go up in flames, and by 1945 European Jewry would go up in flames. The Prophets had something to say. Has Judaism in this moment silenced them while claiming to be speaking for them? Maybe this should be the Fifth Question at the Seder.

Chag Herut Samaekh

Shaul

I have so many thoughts. First, I can’t believe he said all those years ago that the nation Israel could also become an idol, as many are saying today. I love that. Also, I have been thinking lately what a dangerous thing, ironically, it is that this “jewish state” is so secular/non-religious, leaving out all the Jewish values that come from the “religious” part of it for the sake of nationalism, being Jewish just for the sake of—nothing? Victimhood?—which is indeed dangerous—as we are seeing.

I'm wondering if there's a downloadable haggadah emphasizing liberation appropriate for this year's seder. Anyone have recommendations? Help much appreciated.