"Why Jews Have Such a Hard Time Talking about Antisemitism?" Part III - The Question of Holocaust Uniqueness

Is the Holocaust a unique event in Jewish, and world history, and why that matters in the discussion of antisemitism and Israel

In the first part in this four-part series, I asked the question: “Why Jews Have Such a Hard Time Talking about Antisemitism?”. I suggested a triad that includes the argument over the eternal nature of antisemitism, the uniqueness of the Holocaust, and state exceptionalism that follows from how one understands the first two.

In the second post I wrote about the question of “eternal antisemitism” and the way it creates a barrier between Jews who believe in it the eternality of antisemitism, and this who don’t. For those who have not seen Part II, I recommend you read it.

In this part (Part III) I address the question that has been at the center of Holocaust Studies for decades, that is, was the Holocaust a unique event in Jewish, or world, history? In many ways this underlies “post-Holocaust theology” initiated by Richard Rubenstein with his After Auschwitz published in 1966 and then myriad studies by Emil Fackenheim, Eliezer Berkowitz, Irving (Yitz) Greenberg, Steven T. Katz, Yehuda Bauer, Robert Wistrich, and many others. This is not the place to delve deeply into the complex contours of the debate. For that I suggest Zachary Braiterman’ s (God) After Auschwitz: Tradition and Change in Post Holocaust Jewish Thought (Princeton University Press, 1998).

My interests here are narrower and about the general discussion of “uniqueness” and the way it informs how people understand Zionism and the state of Israel. The link between the Holocaust and the state of Israel is itself a matter of debate. On the one hand there are those who justify the state because of the Holocaust, those who think the Holocaust was the theological precursor to the state (Zvi Yehuda Kook et al), and those who think there is no theological/religious connection between the Holocaust and the state of Israel (e.g. David Novak and Yeshayahu Leibowitz).

Intense focus on the Holocaust as a lens to view developments in Jewish identity and Jews relationship to Israel, began in earnest in the early 1970s. The question regarding the Holocaust’s uniqueness was a prominent part of that post-Holocaust theorizing, an expression of competing desires of American Jews to be fully integrated, yet definitively distinct, in American society. It remains so today.

As has been noted, the term “uniqueness” in general is problematic as an analytic term. Conceptually, it arguably has little meaning and is used, or proclaimed, to support one’s position on other matters. (Steven T. Katz’s multi-volume The Holocaust in Historical Perseptive seeks to make uniqueness a historical claim). For example, Peter Novick remarks, “Insistence on its uniqueness (or denial of its uniqueness) is an intellectually empty enterprise for reasons having nothing to do with the Holocaust itself and everything to do with ‘uniqueness’. A moment’s reflection makes clear that the notion of uniqueness is quite vacuous.” Earlier Ismar Schorsch wrote, “…unique is a description that responsible historians tend to employ only in a restricted context. Used indiscriminately, it is a throwback to an age of religious polemics where commitment was largely a function of uniqueness. Unfortunately, our obsession with the uniqueness of the Holocaust smacks of a distasteful secular version of chosenness. We are still special – but only by virtue of Hitler’s paranoia.” Uniqueness seems to me to be largely a placeholder for other meanings that are in play when those positions and debates are identified.

Uniqueness advocates from the 1970s to the present may be more interested in what the term produces than the term’s conceptual coherence. Theologically, uniqueness refers to an event that cannot fit into any previous theological paradigm (think of the theophany at Mt Sinai) and is thus unanswerable with traditional theories of theodicy. The historical debate about uniqueness is much more polemical and, it seems to me, largely divided according to ideological camps. For example, if the Holocaust as genocide against the Jews is unique and thus an exceptional case in human history (the term genocide coined by Polish-Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin around 1941), perhaps the case of the Jews after the Holocaust (re: Israel) can justifiably inherit that exceptional status, which is what uniqueness implies. In any case, uniqueness is an argument that arguably thrives on a stable foundation of ethnicity. As Jews increasingly own multiple ethnic identities or identify as Jews separate from that a singular ethnic affiliation, we may need to reassess the function of such a concept.

If we abandon the claim of uniqueness, we can posit that the Nazi genocide of six million Jews was a tragedy of world-historical proportions, but it would not be “the Holocaust.” The uniqueness claim presents certain challenges to the historian. One problem is that to argue for uniqueness too easily lends itself to taking an event outside the realm of history, making it what the Jewish theologian Arthur Cohen called a mysterium tremendum that in many cases results in a kind of mystification. Mystification too easily relegates the Holocaust to a purely “religious” and not a historical event (one could think of how Christianity defines the crucifixion in similar terms). And if we then link the Holocaust as an ahistorical event to the nation-state called Israel, it is too easy (although not necessary) to import the ahistoricity to a functioning nation-state and member of the United Nations. While there are in the religious Zionist camp many who want to do that, most Zionists would blanch at such a claim and yet in some way tacitly support it.

Yet, even given this challenge, many historians argue that the Holocaust is a unique event, in both Jewish and general history. In doing so the historian must defend how something can be both a novum and historical. And by extension given its connection to Israel how Israel can be both a novum and historical. Holocaust historian Yehuda Bauer maintains the Holocaust is a historical novum and simultaneously warns against using the Holocaust’s uniqueness toward its mystification. He writes, “It is necessary to dispel mystification around the Holocaust, if only to clear the way for the historical perspective.”

While Bauer ultimately comes down on the side of uniqueness, he remains acutely aware of the way uniqueness can produce a kind of mystification that works against what many Holocaust scholars want: the memory of the event to remain. As a historian, Bauer knows that “The inevitable conclusion must again be that if we label the Holocaust as inexplicable, it becomes relevant to lamentations and liturgy but not to historical analysis.” Uniqueness elides history and this will lead to mystification which, according to Bauer, will result in “forgetting.”

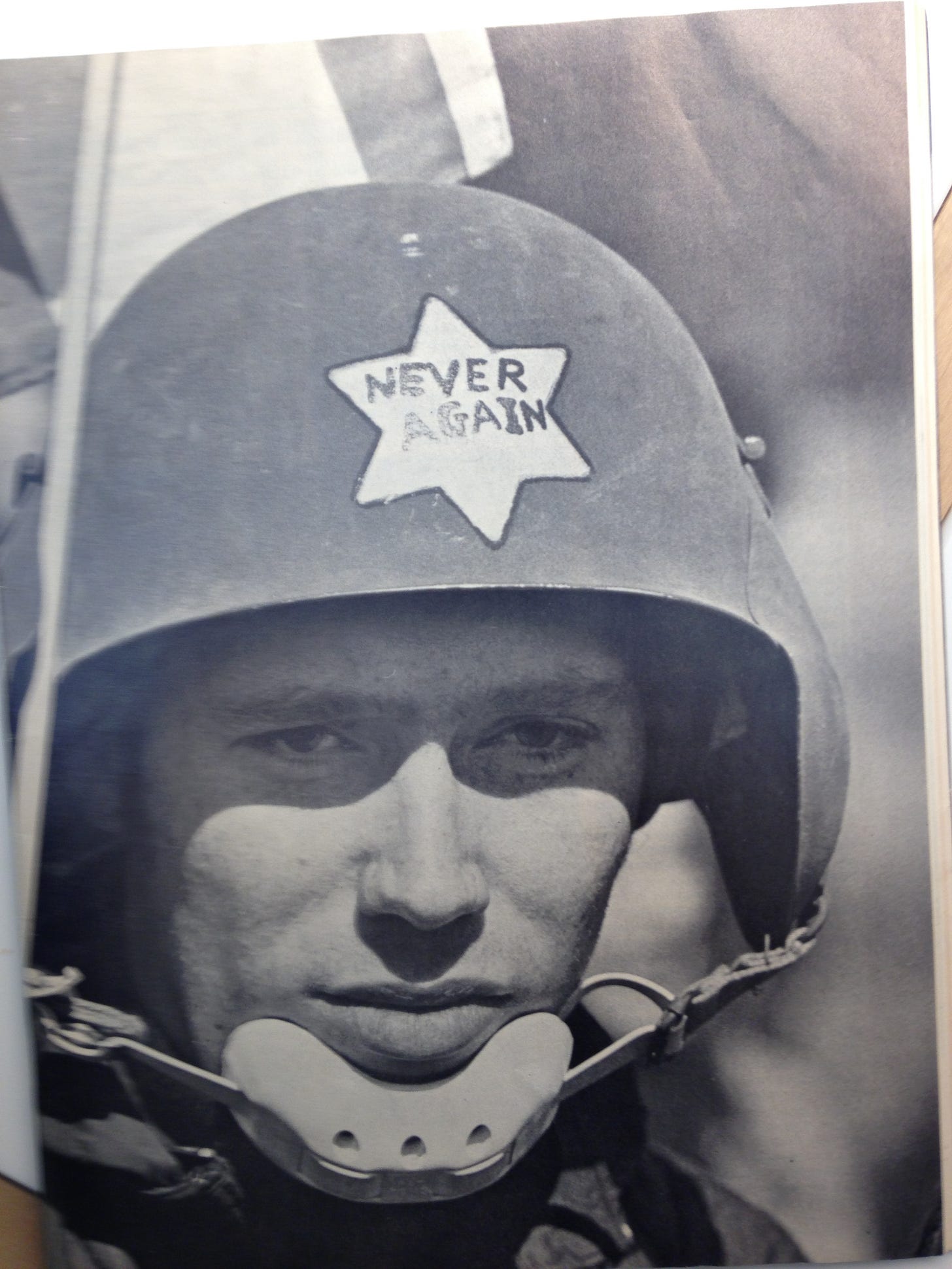

The fear of repetition (baldly pronounced as a political platform in Meir Kahane’s 1971 “Never Again!”) is arguably still the emotional engine that drives much of the discourse about the Holocaust today and about Israel. There are those who argue that the while the Holocaust as a historical event ended in 1945, as a meta-historical phenomenon it never really ended. In this view, contemporary antisemitism, in Europe and now in the Muslim world, is an extension of the antisemitism that produced the Holocaust. We can see this the way Holocaust analogies emerged a few days after October 7th even though October 7th occurred under Israeli/Jewish sovereignty and the Holocaust occurred while the Jews were in a powerless state living under the sovereignty of others.

Without some variation on the view of something being “unique” and “historical,” that is, it can occur again it is difficult to hold the Holocaust’s uniqueness and its possible repetition simultaneously. That is, to argue today about an impending Holocaust while maintaining the Holocaust as a unique event in human and Jewish history may be implying, intentionally or not, that the first Holocaust never really ended. This is not such a far-fetched position among many who defend Israel’s exceptionalism, as we will see in Part IV of this exercise.

While the historical and theological questions regarding uniqueness are shared by American as well as Israeli Jews (for whom the Holocaust plays a very different role), the question of the particularistic as opposed to the universal message of the Holocaust is more specific to the American context. This is due to two interlocking reasons. First, Jewish identity in America is inextricably tied in complicated ways to American identity. Like other integrated minorities, American Jews are hyphenated creatures. Second, as indicated by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., the Holocaust is part of both Jewish and American history. As a result, exclusive Jewish ownership of the Holocaust is a vexed issue in contemporary America. Alternatively, in Israel the Holocaust is the final chapter in its myth of origins and thus has little use for universalizing the event. Israelis also understandably seem less invested in calling the Holocaust unique. By referring to the Holocaust as “the third churban” (der dritte churban) and the State of Israel as “the third commonwealth” Israelis are viewing the catastrophe, and the subsequent triumph, as part of and not categorically distinct from the Jewish past.

What I want to suggest here is that as conversations about antisemitism or Israel break down among American Jews today, in families, synagogues, communities, and campuses, if we would take account of how the parties think about the claim of Holocaust “uniqueness” (admittedly many American Jews don’t really think in those terms) we might find those differences have an impact on the issues of the day.

To rehearse what I stated above, if you believe that (1) the Holocaust was a unique event (uniqueness as unprecedented); and also (2) that the Holocaust in part of history, and thus can be repeated, and (3) you think there is a strong link (historical, political, theological) between the Holocaust and the state of Israel, then (4) one could easily posit Israel as a “exceptionalist” state that not only should not, but cannot, live by the standards of other states. The problem with this, of course, is that by making Israel an “exception,” it feeds right into the double-standard argument which is deemed antisemitic, albeit in reverse (we will deal with this in Part IV).

The question of the uniqueness of the Holocaust is an issue separate from Israel. But it is also an issue that implicates Israel in all kinds of ways, overt or covert. Meir Kahane’s popularization of the term “Never Again” was a meme that extended beyond his militant Zionism. It was also worn on the helmets of Israel soldiers in the 1967 war be. fore Kahane breakout book by that title in 197. It seemed to be a term that was used in kibbutzim in the 1950s. (see photograph above).

There are numerous ways around this. First, to deny the Holocaust as unique and see it as perhaps the most horrific event in known history but not transhistorical. (By the way David Ben Gurion did not want to see the nascent state as contingent on the Holocaust). Second, to maintain the Holocaust is unique but claim it has no religious meaning in relation to the state of Israel. This is the position of David Novak in his essay “Is There a Theological Connection between the Holocaust and the Reestablishment of the State of Israel?” in the volume The Impact of the Holocaust on Jewish Theology edited by Steven T Katz. Third, to claim the Holocaust is unique and thus in some way never fully ended, contemporary antisemitism being an extension of the Holocaust (thus calling Hamas, Nazis), thereby extending the exceptionality of the Holocaust to the political (and historical) exceptionality of the state of Israel.

Each of these positions yields something different regarding how one understands Israel as a nation among nations, its responsibilities as a sovereign state, and the particular way it views its enemies. For example, if one accepts the Canadian Member of Parliament Irwin Cotler’s view that Israel is “the collective Jew” (this is also the position of French intellectual Alain Finkelkraut and others) then the nation state is not a normal state (which was the very raison d’etre of Zionism, to be “like all the other nations”) but an exceptional (and thus abnormal) state that cannot abide by the rules of nation-states.

I claim here that, not dissimilar to the question of “eternal antisemitism,” the “Holocaust uniqueness” question can help us better understand why it is so difficult for Jews to talk about antisemitism today. In Part IV I will directly address the exceptionalist question regarding the state of Israel among its supporters.

Thanks for this. I like to make a distinction between "being Jewish" and "doing Jewish." In a similar vein, there's the Holocaust (which perhaps was unique depending on everything you outlined above) and "perpetuating this or any other holocaust" by or against Jews. Where do "holocaust" and "genocide" interact? If Nation A proclaims its intention to eliminate a certain ethnic (or religious) group, and succeeds even in part (as Hitler did) would this be called a holocaust? or a genocide? or ignored altogether because we don't care about the victims of Nation A? So: could we be "doing a holocaust" by committing genocide? Thanks again...I look forward to part IV.