[note: As the Book of Esther states, Purim was celebrated on the Adar 14 in the provinces, and Adar 15 in Shushan, the capitol, because of the time lag in communicating about the Jews’ victory to avert the king’s decree. Since Shushan was a walled city, the custom of celebrating Purim on Adar 15 in walled cities at the time of the story, was established. Being a walled city at time, Jerusalem celebrates Purim on Adar 15, known as “Shushan Purim,” whereas everyone else in Israel and the Diaspora (as far as I know) celebrates Purim on Adar 14.]

The biblical mandate to “remember” and to “wipe/stamp out” Amalek is at the center of the ritualization of Purim, marked by the practice of shouting and stamping one’s feet every time Hamas is mentioned in the public recitation of the Book of Esther, Hamas viewed as the progeny of Amalek. There is even a clever and amusing Eastern European custom to write the word “Amalek” on the soul of one’s shoe, so that every time you take a step you are “stamping out Amalek.”

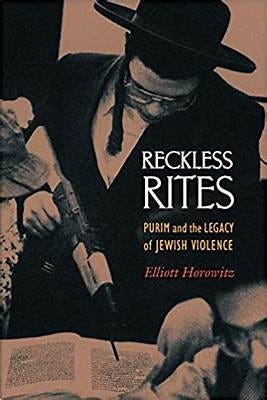

This reference to the genocidal commandment to “wipe out Amalek” has been the cause of violent fantasies throughout the Jewish tradition, as examined extensively by Elliot Horowitz in his book Reckless Rites: Purim and the Legacy of Jewish Violence (Princeton: 2008). It came to a tragic crescendo on February 25, 1994 when Baruch Goldstein, an American Israeli settler, woke up before dawn on Purim morning and, with the commandment to destroy Amalek on his mind, walked into the Cave of the Patriarch Mosque in Hebron, and slaughtered over 30 Palestinians worshippers in prayer. His gun then jammed, and he was attacked by the crowd and killed.

The notion that “remembering to blot our Amalek” is an act of violence in potencia, has been with Jews since its inception, as Horowitz notes in his book, citing hundreds of examples. While relegated to realm of fantasy for most of Jewish history, when Jews achieved sovereignty in a nation-state that potencia could easily become, and in some cases has become, actualized. Thankfully, this has only occurred intermittently among militant factions in Israel. But the sentiment is there and the move from fantasy to reality is not a great leap. In some way October 7 may have sent that into overdrive.

But what if “remembering Amalek” is not about Amalek’s hatred of the Israelite/Jew? What if the object of remembering is something else entirely. And what are the implications if we are missing what we are mandated to “remember,” misplacing it with remembering the hatred by another which, as we see, reciprocates as the hatred of that other?

Below I present my translation of a Hasidic text Divrei Yoel built on a medieval midrash that offers an entirely different understanding of “remembering Amalek” that radically shifts our orientation of what Purim should be about. After the text I will offer some reflections.

Text:

It is worth beginning with a passage from Pesikta (#12) Remember what Amalek did to you…

To what can this be likened? To a king who has an orchard and a guard dog who keeps watch over the orchard. A son of the one the king’s beloved subjects comes to steal from the orchard. The dog attacks and bites him. When the king wants to remind this child that he wanted to steal from his orchard, he says to him “remember what the dog did to you.”

So, Israel was sinning in Refidim, as it says, The place was named Massah and Meribah, because the Israelites quarreled and because they tried God saying, “Is God present among, us or not?” (Ex. 17:7). Immediately the dog came to bite them, this is Amalek, as it says, Amalek came to fight Israel in Refidim (Ex 17:9). [here the midrash ends].

[Teitelbaum comments] From this midrash we can learn that the “remembering” is not to remember the hatred of Amalek toward the Israelites because [following the parable] Amalek justifiably came upon Israel as a punishment. Rather, the reason for “remembering [Amalek]” is that Israel should remember the sin [that brought Amalek upon them]…

One can add an additional dimension here. We read in Beit Yosef [Joseph Karo’s commentary to Tur Shulkhan Arukh “Laws of Shabbat” # 242] about the Talmudic dictum “One who observes the Sabbath, even if they are an idolater like the generation of Enosh, they will be forgiven.” [on the sin of the generation of Enosh see Maimonides “Laws of Idolatry 1:1 in his Mishneh Torah, vol. 1].

The reason is that Shabbat is equal to all the other mitzvot because it testifies to God as creator and God’s providence. Therefore, one who observes Shabbat the idolatry that they commit can’t really be sincere, that is, they can’t really believe in it [since observing Shabbat by definition undermines any other divinity, ed.].

One can say of this that by observing Shabbat one becomes bound to Shabbat itself, and this will have a tremendous impact on one’s faith in God and thus make it impossible to believe in any form of idolatry.

Back to our original point [about remembering Amalek], the fundamental nature of the sin “Is God present among, us or not?” (Ex. 17:7) is a blemish in faith (emunah). However, if the Israelites had been observing Shabbat, they would have bound themselves to its implications [God as creator and providential] which would have profoundly affected their faith. In that case, not only would that sin [of idolatry, Is God present among, us or not?] be forgiven, it would have been totally uprooted from them.

R. Yoel Teitelbaum, Divrei Yoel on the Festivals, vol. 6, 288, 289

Comment:

The midrash offers a radical alternative to the biblical mandate to remember Amalek. In the parable of the king, Amalek, likened to the guard dog, attacked the son because he was engaged in theft. That is, the dog was an appointed by God to protect God’s orchard and, in that sense, was acting on his mandate [even if he attacked him mercilessly]. What the king does is to remind the son (the thief) that the consequences of his actions brought about the terror of the dog. That, the midrash suggests, is “remembering Amalek.” By remembering Amalek, we can remember the sin that created the conditions for his attack.

Teitelbaum develops this a bit more, adding on the layer of Shabbat as a testament to divine omniscience and providence. He also follows the voice of the midrash and redirects the “remembering” of Amalek to the actions that brought about Amalek. The question Israel asks, “Is God present among, us or not?” (Ex. 17:7) is a question that reaches down to the very fundamental principles of faith (divine omniscience and providence). Once that question becomes operative, faith is deeply tarnished, and Amalek attacks, like a dog guarding the orchard. It is interesting, perhaps ironic, that the parable is about theft, where our situation also revolves around conflicting claims of theft and ownership, but I will leave that to my readers’ imagination.

On this reading, both in the midrash and in Teitelbaum, Purim is not a day of justifiable vengeance the way we view it in chapter nine of the Book of Esther, but a day of repentance and reflection on what Israel may have done to bring about such ostensibly unwarranted violence [it is the midrash that describes Amalek as “punishment”].

In my previous post on Purim, I argued against equating Hamas to Amalek on both situational and philosophical grounds. Here I suggest that even if we want to equate Hamas to Amalek, this midrash and Teitelbaum’s reading undermines the reaction. If anything, October 7 should evoke, considering the midrash, an introspection of whether in some way, “Is God present among, us or not?” is operative and what that might mean in our time?

To deflect the accusation of “blaming the victim,” I am not suggesting somehow Hamas should be exonerated from their massacre of men, women, and children, nor is the midrash exonerating Amalek. Hamas is guilty of mass murder that is not an exercise in legitimate resistance. Resistance to occupation is legitimate. But like everything else, resistance also has its limits.

But it does not stop there. The midrash [and Teitelbaum] suggests that belief in divine omniscience and providence (in Teitelbaum claims is embodied in the observance of Shabbat) should evoke a belief in divine-human reciprocity. And it is precisely this “divine-human reciprocity” that exercises the midrash.

The notion that Oct 7 has no October 6, that Israel had no part in creating conditions that made October 7 possible, that occupation, siege, land confiscation and dispossession were not part of the last half century of Israel’s actions toward the Palestinians, is all too common, now more than ever. The unmitigated “evil” of Amalekite behavior implies unmitigated “innocence” on the part of its victims. While understandable given the ferocity of the tragedy, this midrash, and Teitelbaum’s gloss, suggests such a reaction is a serious misreading of Purim. Or, alternatively, it is founded on a deeply flawed sense of belief, e.g. “Is God present among, us or not?” which can be embodied as much by the religious sector as the secular. A bigger question for another time is the extent to which religious belief today on this question is itself based on secular assumptions, i.e. “God will not redeem us, we will redeem ourselves.”

The guilt of Hamas’ action is on their head, and protecting oneself from violence is both legitimate and necessary. But by not taking the additional step of examining if and how “Is God present among, us or not?” as covenantal part of any Jewish project, nationalist or otherwise, leaves us vengeful, frightened, and thus prone to a repetition of the cycle that brought us here, heaven forbid.

Good Shushan Purim

קלע/קלעת אל השערה

“Is God present among, us or not?”

Is the placement of the comma intentional? As in, would it not make more sense? “Is God present among us or not?” as opposed to, twice you have noted here: “Is God present among, us or not?”

I would love to know the reason behind it, if it's indeed intentional.